7 May 2014

Posted by Michelle in Expat Life, Language | 0 comments

So you’re thinking of raising your children bilingually – there are many strategies for achieving this very worthwhile goal, so read ahead and I’ll go into details of each of the popular methods.

It’s generally understood that if children are exposed to a language for 30% of their time they will pick the language up, but it’s important to keep in mind that this isn’t just 30% of the time for a year or two, it’s constantly. The key to learning and maintaining language is to use it consistently over a long period of time.*

One Person, One Language (OPOL) Method. Sometimes written as the One Parent, One Language method.

You’re a native Japanese speaker living in Amsterdam and your partner is Dutch – you both decide to speak to your child in only your native tongues, this is the OPOL method in action.

This is very popular and as the name suggest, one person usually one of the parents speaks a language with their child while the other parent speaks another language to the child, thus raising the child bilingually. If it’s not the parents it might be a grandparent, an Au-pair, school teacher and so on. One of these languages might be the language of the country the family is living in, or it might be that you are speaking two minority languages at home and the children learn a third in school.

Sometimes children can be sneaky and realise that ‘hey, if I speak Dutch to mum she understands me and I can escape from learning Japanese and spend more time playing computer games. Win!’ Here is where it helps to be very consistent, you might simply say in Japanese that you don’t understand, or respond in Japanese. What is most important is instilling in your children the importance of the second language, especially if it’s tied to their cultural heritage – this way they are more likely to see the need and develop a desire to speak the language, rather than seeing it as a waste of time. Trips to countries in which the language is spoken can help here too (see Time and Place method), especially if they are able to interact with cousins and grandparents who only speak one language.

You can read my interview with Professor Christof Demont-Heinrich about how he is raising his children in German and English using the One Parent, One Language approach – the very interesting this here is that Christof isn’t a native speaker of German (although his father was) and yet he is successfully raising his children to be bilingual. This is one of the positive sides to this approach – you don’t necessarily need to be a native speaker of the language – although if this is the case it might help to supplement with a tutor or Au-pair who can help with grammar and pronunciation.

Minority Language at Home (mL@H) Method

Say you’re living in Germany for work but you are originally from the UK – you might choose to send your children to a local German school so they can pick up the language and culture while speaking only English as a family at home. This is the Minority Language at Home method, because your family language is not the dominant local language.

This is a very popular method, both by choice and by necessity for many families around the world. It’s an effective way for your children to become bilingual – just keep in mind that this might mean your children are fluent in relaxed conversation, but it could be a very different story if they had to write an essay in the language.

I was interviewing a Finnish woman a couple of weeks ago who grew up in a number of different countries and attended international schools in English – she had recently read back her first university essay in Finnish and was amused and a little horrified to find that it sounded like she was chatting to someone in a club. Having spent the majority of her formal education in a non-Finnish environment, it meant by the time she reached university her academic Finnish was not as good as her English, despite Finnish being her mother tongue and the language she used at home every day. I’ve heard this happen time and time again, so it’s really important to make sure your children practice academic writing and are exposed to literary, political, academic, etc works in both languages (written and spoken).

Time and Place Method

This method is best used in combination with those above.

You might live in the USA but have a deep passion for the Chinese language and culture, spending long summer breaks there each year with your children where they play with local children in Mandarin and maybe even attend an immersion language program there. You think wistfully of China back home in the USA, but you don’t necessarily speak the language with your children – you just make an effort to visit China as often as you can.

Obviously this method might not be as effective as the OPOL or mL@H method, simply due to lack of time spent immersed in the language. There are of course ways to supplement this with a more mixed method – say T&P + OPOL for example a Mandarin speaking Au-pair, children attending an English-Mandarin bilingual school or play group, and so on.

So what is the best method?

That is up to you, your family and your circumstances. Some people might not feel comfortable speaking to their child in any language but their mother tongue, meaning that if both parents are Australian and they live in Australia, obviously Minority Language at Home is ruled out. They might then choose to send their child to a French/English bilingual school making use of the OPOL method and supplement this with a trip to France every few years, or sending their child on exchange during high school for a year.

It’s about finding a method that feels right for you, researching it (books, blogs, forums), experimenting and being consistent.

* Read Raising a Bilingual Child by Barbara Zurer Pearson for more information on this topic – it’s an excellent book!

Are you raising your children bilingually? What methods do you use?

27 Aug 2013

Posted by Michelle in Expat Life, Language | 2 comments

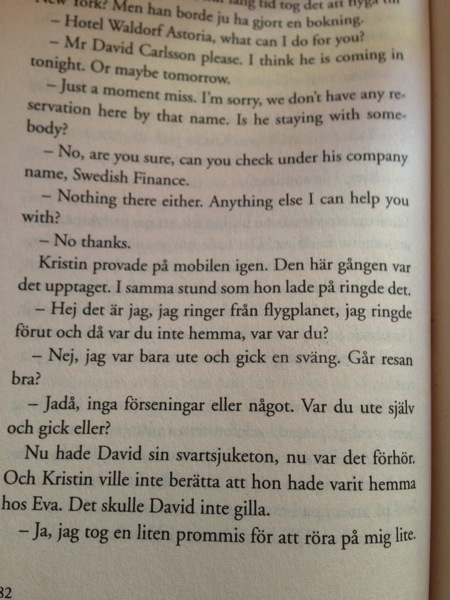

I’ve been reading a Swedish novel over the last two weeks and found something quite interesting. At one point in the book the protagonist calls up the hotel her husband is supposedly staying in in New York – but the interesting thing for me was that the novel simply switched to English when she made the call rather than continuing on in Swedish.

According to the 2012 Eurobarometer report on Europeans and their languages, 86% of Swedes (and Danes) say that they speak English well enough to have a conversation. Only the Dutch at 90% and the Maltese at 89% have a higher rate of English language ability in Europe.

For me, the assumption is clearly that Swedes will all understand English well enough for this language swap to be completely acceptable. I’ve occasionally seen the odd French phrase included in English language novels, particularly when reading the classics, but never entire paragraphs, and certainly never in chick lit novels such as the one I found this example in (Väninnan by Denise Rudberg).

Have you seen other novels with entire paragraphs in another language? I’m really curious to see whether this is a common theme around the world, or if it is simply because the Swedes are so confident in their English language abilities. I wonder if it is also the case in Dutch books too.

2 Nov 2012

Posted by Michelle in Expat Life, Identity, Language | 3 comments

I’ve been lucky enough to be able to interview Christof Demont-Heinrich, Associate Professor of Media, Film & Media Studies at the University of Denver about his views on bilingualism, and also his experiences of raising bilingual children.

I first came across Christof on the brilliant sociolinguistics website Language on the Move where I was immediately fascinated by his articles on the costs of raising bilingual children in the United States. What is interesting about Christof is that while his father was German, Christof was raised to speak only English, and learnt German later at university. He now uses the one language one parent approach to teach his two daughters German and English, but as a non-native speaker of German, he has also employed at various times German au pairs, a nanny and then sent his daughters to an international school in the US.

Michelle: Some people from English speaking countries feel that due to English being the (unofficial) lingua franca of the world at present, that being bilingual is unimportant for native English speakers. Why was it important for you to raise your two daughters to be bilingual in the US?

Christof: I believe strongly in the ideal/ethic of meaningful multilingualism for all, including mother tongue speakers of English. I also believe that simply talking about how important multilingualism is — which a lot of well-educated mother tongue speakers of English do — but not actually living that multilingualism in a meaningful way is highly problematic. We need to live that which we preach/believe in, create the social structures and practices we believe in by living them, or they will not come to be. Plain and simple. I recognize this is highly idealistic, of course, and the fact of the matter is that, while a small but also growing percentage of the U.S. population with English as a MT are waking up to the fact that multilingualism has to be lived in order for the ideal to survive, for instance, by building language immersion schools, the vast majority of people for whom English is a MT in the U.S. either have little interest in multilingualism, or, if they do, do not bother to invest themselves significantly in building the social structures and participating actively in the social practices needed to develop multilingualism in a meaningful way.

In short, while I recognize — in a painful way, actually — that instrumental language learning means that very few mother tongue speakers are going to invest in becoming meaningful multilinguals themselves, I want to build a world in which this changes, even if very slowly. I view myself, and the bilingual living and education of my daughters as integral to actively building the multilingual social change I believe in. I’m not so naive as to believe that we, alone, will change much of anything. But if enough people “walk the walk”, then, hopefully, change will happen on an incremental basis. Of course, being somewhat of a natural born pessimist, I often think that what I’m doing is rather hopeless.

Why did you choose the combination English/German?

C: For heritage reasons. My father emigrated to the U.S. from German in the early 1960s. He did not pass his linguistic heritage on to me or my two siblings (my mom is an American who was, when we were kids, an English monolingual). We lived for 8 months in Stuttgart, Germany when I was 7. I went to school then, along with my younger brother, who was 6. I acquired something very close to a native accent as a result of this well-timed experience. However, I never really learned German until college (the late 1980s), when I chose to major in German and I spent a full year studying abroad in Freiburg, Germany.

Why did you choose the one language one parent approach? Would you recommend this approach to other parents who might not be a native speaker of the language?

Everything I have read — and I have read extensively on the topic of raising children bilingual — points toward this being the most effective approach, at least if the goal for the children to use the minority language regularly on an everyday basis and, ideally, acquire high-level spoken fluency in that language (I recognize this is not always the goal for all parents raising their children as multilinguals, that there is a continuum of goals/hopes for the children ranging from a “a few words/sentences” and simply a general appreciation of the minority language to receptive bilingualism only to full-scale, near “equilingualism” for the children. I believe my stubborn and consistent sticking to German — which, as you probably know, is not a first language for me — with my daughters, Alina (7) and Kyra (6) has been absolutely integral to them using German everyday. I’ve seen many situations in which parents, for a variety of understandable reasons, do not stick to one parent one language and, in those case, I see that the children often speak very little German at all. While I think one parent, one language, and sticking to that is absolutely crucial if the goal is high-end spoken fluency and regular use of the minority language and the family situation is one in which only one parent speaks the minority language (that is our situation), I think an even better situation is one in which both parents speak the minority/less powerful language in question, for instance, German in the U.S. In those instances, I would support a two-parent German at home model, frankly.

What have you found most challenging/rewarding?

In terms of challenges, fighting the system, frankly. The entire U.S. public education system is rigged against multilingualism and for monolingualism. Indeed, it’s specifically designed to ensure the erasure of the languages of immigrants who are educated in English only. Because there is only a tiny percentage of public charter schools in the U.S. that offer language immersion program — far less than 1% of schools in the U.S. offer language immersion — and because “our” language, German, is not a powerful language in the U.S. context, we have been forced to send our kids to a private language immersion school. I’ve estimated by the time my daughters are 13, we will have spent $250,000 out of pocket on their bilingual education. This because the American public education system simply does not support bilingualism. Nor does the larger American values system — if we truly valued meaningful, deep multlingualism for all, we would see that reflected in investment in multilingualism in our education system. The monolingual U.S. public education system is nested within a cultural and political environment that is largely indifferent, often very antithetical, to multilingualism, especially actually lived, everyday multilingualism where people actually use multiple languages on an everyday basis in multiple domains outside of the home.

Are there any books or journal articles you would recommend for other parents wanting to raise their children to be bilingual?

I’m going to have to check on this. While I’ve read quite a few, I haven’t kept track of them, for the most part. That’s because my area of research as a professor at the University of Denver focuses primarily on macro-level issues having to do with language, identity, power, culture, globalization, and, especially, the globalization of English as this affects the larger global linguistic configuration of power as well as the question of multilingualism vs. English-centric bilingualism (for those for whom English is a FL) vs. English monolingualism (for those with English as a MT).

Do you want your daughters to spend time living in Germany while they are young? (to become familiar with the German culture as well as the language?)

Yes. In fact, I hope to be spending a sabbatical year at the University of Hamburg with the entire family next year. I hope that everything works out and we are able to do this. Of course, I am aware of the rather large irony that in order to raise my kids as true/meaningful bilinguals I must escape the deep monolingualism of the U.S. education system and place my kids in the largely German monolingual educational environment in German.

Yes, they are clearly learning English in Germany, the students, that is, and they start at a much earlier age than children here do on learning FLs. But in the end, the general environment in Germany, I would say, is still one in which the ideology of monolingualism, in this case monolingualism + English, dominates, e.g. the “modern” nation state model. I ultimately view as the biggest impediment to meaningful and deep multilingualism for large numbers of people around the globe. That is, English isn’t really the problem, it’s the ideology of monolingualism that’s the problem. In global power domains this translates into English only — at academic conferences, etc. However, it could just as easily be another language, had historical circumstances developed differently. And, frankly, I often wish they had (though, clearly, I would not have wanted to see Nazi German triumph — that’s a whole other issue, Germany’s Nazi past, that complicates the whole attempt to raise one’s kids as German-English bilinguals: The vast majority of German educated elites see English as an escape from that past — and I, and my daughters, are literally swimming against all the Germans rushing to English in our attempt to be German-English bilinguals). In any case, if another language had become the global language, then we Americans would be multilingual — because we’d have to be.

Thank you very much Christof!

You can read more about Christof’s views here at Language on the Move.

27 Aug 2012

Posted by Michelle in Expat Life, Language | 2 comments

There is a Czech proverb I love which means: ‘You live a new life for every new language you speak. If you only know one language, you live only once’.

Image by Zsuzsanna Ilijin

Image by Zsuzsanna Ilijin

In much of the world, bilingualism and even multilingualism is the norm. The 2012 Eurobarometer report revealed that 98% of Europeans considered bilingualism to be important, and on average, 54% of Europeans are able to hold a conversation in a language other than their mother tongue. But in primarily English speaking countries fewer parents are raising their children to be bilingual. The fact that English is so widely spoken around the world is one of the main reasons for this, giving those of us with English as our mother tongue less of an incentive to learn another language to fluency. But bilingualism and multilingualism have numerous cognitive, cultural, and professional benefits for you and your children.

The benefits of bilingualism include:

- Creates a connection to your children’s cultural heritage, particularly important when parents come from two different cultures. This also means children can communicate with grandparents and other relatives who might not speak one of their languages;

- Ability to build friendships with a wider range of people, read the literature of that language in its original form, watch films in the language, and be exposed to a greater number of ideas and perspectives;

- Strengthening of cross cultural communication skills;

- Increased empathy: research by Princeton psychologists Paula Rubio-Fernández and Sam Glucksberg have shown that bilingual children are better able to put themselves in the shoes of others and understand a different point of view;

- Increased cognitive abilities, for example more effective multitasking: bilingualism decreases confusion when switching between tasks;

- There is increasing evidence that bilingualism can help to cope longer with Alzheimer’s: In a study of 200 Alzheimer’s patients, cognitive neuroscientist Ellen Bialystock revealed that bilingualism resulted in a 5 year delay of the onset of Alzheimer’s compared with monolingual patients. So while bilingual people still develop Alzheimer’s, they are able to better cope with the disease for longer, and function at a higher level than those who are monolingual.

- Bialystock also discovered that bilingual children also process language differently: for example she asked a number of monolingual and bilingual children whether the sentence “apples grow on noses” was grammatically correct. While a number of monolingual children became caught up in the silliness of the sentence, bilingual children were often able to establish that while the sentence did not necessarily make sense, it was in fact grammatically correct. This is because bilingualism can effect the executive control system, or rather bilingual children have an increased capacity to tune out noise while focusing on what is relevant;

- Career advantages: more and more jobs require a minimum of two languages. Want to work for international organisations, or the EU? Some of these jobs require three or more languages, or at least put you at a distinct advantage compared to monolingual candidates. Professors Louis Christofides and Robert Swidinsky discovered that in Quebec, Canada, men who speak English and French earn on average 7% more and women 8% more than this who speak only French.

Bialystock does note that for the positive effects of bilingualism to be in effect, one must use both languages constantly, and not simply dusting off German or French learnt at school once every 3 or 4 years or so while on holiday. Bilingualism is exercise for the brain, and brain needs constant training to retain these fitness benefits.

Are you bilingual? Are you raising your children to be bilingual? Let me know or send me an email, I’d love to hear about your experiences.