Currently Browsing: Expat Life

17 Jul 2013

Posted by Michelle in Expat Life, General | 1 comment

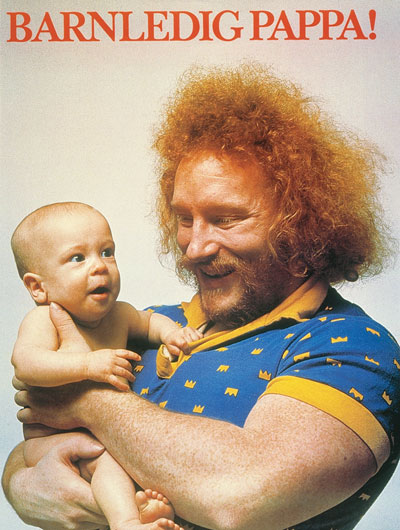

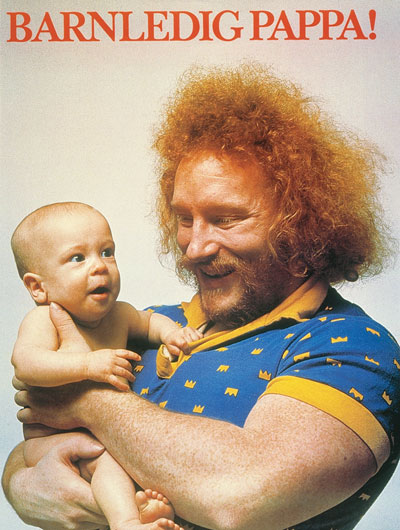

A famous 70’s campaign encouraging paternity leave featuring Swedish weightlifter Lennart ”Hoa-Hoa” Dahlgren

About a year ago I was going for a walk with my friend and while waiting for the lights to turn green at the crossing she turned to say hello to a little baby ahead of us. The man with the baby smiled at us, and hearing we were speaking English said ‘I’m not a gay nanny by the way!’ My friend looked a little shocked, but I could only laugh knowing exactly what he was referring to. Apparently a tourist visiting Sweden had publicly pondered why there were so many gay nannies here, resulting in much amusement by the Swedes because these men were not gay nannies but of course the fathers.

Compared with the rest of the world you’ve probably heard that Scandinavia is the holy grail of places in which to have children: Finland has baby boxes packed full of goodies and one of the best school systems in the world, Norway has paid parental leave at 100% pay for 46 weeks, and in Sweden you’re just as likely to come across fathers on parental leave as mothers.

In Sweden parents receive 480 days of parental leave, of which 390 is paid at the maximum daily amount of 946 SEK or US$143 with some employers choosing to top up this amount. Of these 480 day, both the father and mother are given 60 days of parental leave which only they can take, the remainder being shared between parents as they so choose.

This parental leave is also valid for parents who adopt a child, and parents with twins get an additional 90 days of paid leave. There is even an equality bonus for parents who share parental leave equally. Another important aspect of Swedish parental leave is that it doesn’t need to be taken all at once, but can be used by either parent up until the child finishes her/her first year of school and is available hourly if needed.

In 1995 Sweden introduced a reform to give each parent one month of paid paternity leave that only they could use. By 2002 this had increased to two months each, and there have been subsequent calls for this to be increased to 3 months as in Iceland. Women do still take more time off for children than men do, but these reforms have had a clear impact on the amount of leave fathers take.

Something must be working because I’ve seen more fathers pushing their children in prams here than I’ve seen anywhere else in the world and it’s only been here in Sweden that I’ve seen groups of fathers out together for coffee with their babies.

This gender equality is a huge selling point for highly skilled migrants choosing to relocate to Sweden where work-life balance is of huge importance. I’ve lost count of the number of times I’ve had people tell me that parental leave played an important role in their decision to work for a company in Sweden, especially when one half of the couple is Swedish. The leave for both parents also means that international and cross-cultural couples are able to return to their home country/countries for a month or two and spend much needed time with their families. I know when we have children we will take part of the leave to return to Australia for a few months.

Part of the reason this works so well here is that there isn’t the same peer pressure as in many other countries to work long hours, companies are generally understanding when parents take time off, and if the father doesn’t take his two months of paid leave before the child is eight, the time and money are lost. But it’s important to note that the fathers I’ve spoken to have all willingly chosen to take the leave. They want time to bond with their children and the system in Sweden allows them to do so.

9 Jul 2013

Posted by Michelle in Expat Life, General | 0 comments

Last week I wrote about my experiences as an accompanying spouse, and this week I want to share some tips about some of the things that can help:

Make friends

Building a social network is one of the most important steps to feeling at home in a new country. It’s great to have people to go out for lunch with, to compare experiences with and to have someone you can call when you are trying to work out how to make an appointment with the doctor, or where on earth you can buy a certain item. (this can also lead to an informal importation/swapping service with friends bringing each other ziplock bags from the USA, Timtams from Australia, or chocolate from Germany, etc). If you are looking for work it’s also fantastic to have people you can brainstorm ideas with, to compare interview experiences, and to help one another with CV’s and so on.

When I moved to Berlin to work for 3 months this year, (apart from Geoff) my friends were the main reason I was excited about returning to Sweden. I was surprised to find after my time in Germany that Stockholm was beginning to feel more like home because of the relationships I’d built there.

If you want to read some specific tips about making friends overseas you can read my article. I do want to add that if you have children, this can be an excellent way to make new friends. I know a number of people here who have met new friends in the local park while their children play together, and also through schools and daycares. This is also a great way to meet local friends as well as fellow internationals.

Volunteering and building a network (for job hunters as well)

Volunteering is a fantastic way to become involved in your new community, even if you don’t yet speak the language. It helps you to meet interesting people, to keep busy, and to get some in-country experience on your resume. I began volunteering at a company related to my academic background a few months after I arrived in Stockholm, and it was one of the biggest changes to my life in Sweden. I had a place to go, interesting work, and met fantastic people. This, along with getting involved in different groups and going along to social activities helped me to built a network which has led to work and social opportunities.

Even if you’ve moved to your new destination with the intention to work, don’t forget about volunteering while you hunt – I’ve seen quite a few people end up with work in their industry as a result of volunteering, and they’d never have made those contacts without it.

Communicate

Talk to your partner, talk to your friends and family back home – let people know if you are struggling. Many accompanying spouses don’t want to burden their partner or worry their families back home but it is very very important to let people know how you are feeling.

You might even want to contact a councillor or psychologist, which is a great option when you want to talk to someone independent and better still, professionally trained to help you work through things. In many countries you can chat to your doctor first to get a referral (sometimes these will give you 10 sessions or so for free or a reduced price), but otherwise do a google search and try and find a private one who speaks your mother tongue, or at least a language you feel comfortable in. Try and find someone who has experience working with expats – in Stockholm the Turning Point International Counselling Centre is a great example.

Get to know the local culture

Understanding the local culture can be a very important tool when dealing with culture shock and settling in to a new country. Even if you’ve just moved the short distance from France to the Netherlands there is still a distinct cultural difference you need to adjust to. When you get a feel for how the society works (even if you don’t necessarily agree with every aspect of it) it helps you to feel a little more in control.

If you are interested in cultural differences around the world, my favourite resource is Hofstede’s Dimensions, in particular his book Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind. For a quick overview check out his website for country specific information, but I plan to go into more detail on this topic in a separate post.

Steer clear of negativity

No matter where you go you are bound to meet people who drain the lifeblood from you with their negativity. Just distance yourself from such people, really. My views on friendship are quality over quantity, I’d much rather have a handful of great friends – friends who inspire you, support you, and who you do the same for. The same goes for people who constantly complain about the new country – everyone has bad days but if you meet someone who only ever has negative things to say (the weather is rubbish, the people are weird, the food is terrible unlike back home, etc, etc), then it’s time to move on, or you’ll end up just as depressed. If you think the person might not realise they are being so negative, have a relaxed chat with them about it – if they keep doing it then distance yourself for the sake of your own sanity.

I also want to add that some expat forums fall into this category – some of the comments and very useful but some can make life in your new country seem unnavigable and generally horrible. If you really need to check there for a good dentist, doctor, or a place to buy a vacuums cleaner, then go for it – but nothing very good can come from reading threads such as ‘What I hate about [insert country]’.

Talk to your partner’s HR department

More and more companies are realising the importance of supporting accompanying spouses. Sometimes companies forget to let you know what services they have available to you (this is not a joke – I’ve heard this many many times) – so send an email or give the HR department a call and see what they can do. Perhaps someone will be able to look over your CV and help you update it to better fit in with local job market. At the very least they should be able to direct you towards some online job portals, or perhaps a contact at a recruitment agency. They may also put you in contact with other families.

And if they don’t have any system in place to support you – a few calls might give them the encouragement they need to implement one!

Given the importance of dual incomes and careers today it is unsurprising that academics such as Yvonne McNulty have found that ‘the dual-career issue remains the No. 1 reason for refusing assignments.’ It’s in the company’s best interest to support you.

Give yourself a break

I’ve said it before, but settling into a new country takes time. Be gentle with yourself – you’ll have good days and bad days, and that is totally normal. Take yourself out for lunch or read a wonderful book without feeling guilty for not spending that time job hunting or what have you. Go for a walk through your new city and soak up the atmosphere, it can help you realise the opportunity you have before you.

Do you have any other suggestions for what helps as an accompanying spouse? Let me know below!

2 Jul 2013

Posted by Michelle in Expat Life, Identity | 1 comment

Just over two and a half years ago Geoff and I left Melbourne, Australia and moved to the beautiful student town of Uppsala in Sweden. We moved so that I could take up a scholarship to finish my masters there and luckily Geoff was able to transfer to the Stockholm office of the company he worked for. After I finished my masters, Geoff started working for a Swedish company and we decided to remain in Stockholm for the time being. I might not be a traditional accompanying spouse, but I can certainly relate to the experience on a number of levels.

Accompanying spouses go by many names: trailing spouses and STARs being two of the most common, but it basically means that you’ve moved abroad for your spouse’s career. The 2013 Brookfields’ Global Relocation Trend Report showed that 79% of overseas assigners were accompanied by a spouse or partner, and 43% accompanied by children. While the number of women being sent on international assignments reached a high of 21% in 2012, the vast majority of accompanying spouses are still female.

Having lived overseas of my own volition a number of times in the past has really made me appreciate how very different it is when you do so for your partners career. When I moved alone as a single woman for work or study I could choose where I wanted to go, for how long, and I could choose to move away at a moments notice. Moving as one half of a partnership is still an amazing opportunity: you get to experience a new culture, to learn a new language and to meet amazing people you’d never have met before – all with your best friend, but it does leave you with the feeling that you are somehow not in control of the situation. Although you’ve made the decision together, some sacrifices need to be made, and it is the accompanying spouse’s career that is often the first victim.

Indeed the question that strikes the most fear into the hearts of an accompanying spouse is ‘so what do you do?’ As the brilliant expat writer Robin Pascoe says in response to this question: ‘what did I used to do, what would I like to do, what am I going to do, or what would I like to do to you for asking me this?’ (In an aside, I’d love to have met her at a cocktail party, she sounds fantastic)

Being an accompanying spouse can be challenging. When I had first finished my masters here in Sweden and didn’t have a job, I lost count of the number of times people said “So are you ever going to get a job” – often accompanied by an indulgent smile, as though they thought I must just sit around painting my nails and eating biscuits all day. What is truly frustrating about this is that acquaintances have absolutely no idea of the struggle and heart break you go through on a daily basis when you want to work – looking for work in your field, finding very little in the country in which you are currently living, considering moving to another country, debating whether or not this is a good idea or not, looking for work again. There is often a lot of soul searching, stress, tears, frustration, anger, and sometimes resentment in accompanying your partner overseas. I wanted to shout “You have no idea how hard I am working to try and start a career here”.

At the beginning of this year I took up a position in Berlin working in my field of immigration research. It was an absolute joy to be working full time in a fascinating industry and in a truly enjoyable work environment. But most importantly it gave me a sense of purpose and positive self worth I had been lacking in Sweden. I was amazed by how something so small could have such an enormous impact on me. It gave me the motivation and self confidence to pursue my dream project full time: of interviewing highly mobile children and adults about their identity and to turn this idea into a book.

Choosing to go overseas with their partner is, for many people, the perfect opportunity to spend time on a project they’ve always wanted to get off the ground. I know people who have started successful businesses abroad, who have had the time to dedicate to writing books, who have become freelancers and been able to develop their careers that way, and some who have decided to return to study. I also know some people who have successfully found work in their field (very often people working in the IT industry), some who have chosen to stay at home and focus on raising their families, and some who have decided to simply embrace this time away and to enjoy themselves, knowing that when they return home things will be very different.

All of these are valid choices and should be celebrated.

So if you are an accompanying spouse, please ignore the negative comments you receive. People might dismiss your issues as first world problems or other such nonsense, but as far as I am concerned, life is not a battle to outdo one another in the nonexistence competition of who has the most challenging problems to deal with. It is totally normal to have fantastic days where you can’t help but smile when you realise you live in Stockholm or Paris, New York or Hong Kong. But it is also totally normal to have days when you feel lost, frustrated, depressed and angry. When you find yourself looking longingly at flights home or googling ‘how to make friends in [insert city]’.

Surround yourself with positive people who support you, with friend’s who are going through a similar situation as you, and encourage each other to reach your goals. I couldn’t have gotten through my time here without the support of the amazing women I’ve met here in Stockholm. The support of your partner is also invaluable, but most importantly I think it’s important to give yourself a break, take each day as it comes, and give yourself some credit for having moved to another country and for building a new life there.

13 Dec 2012

Posted by Michelle in Expat Life | 0 comments

Sorry for my disappearance lately – I’ve been travelling quite a bit, meeting long lost family in the Netherlands (and enjoying lovely Dutch food – it is lovely, I tell you!), a week in Berlin and many Christmas markets.

In very exciting news, I’ll be leaving Stockholm in a few weeks to work in Berlin until the end of March. I’m really excited to be going as I love Berlin (a perfect combination of cosy cafes, and history). Geoff will be staying in Stockholm, so I’ll be back and fourth between the two cities.

I’ll post up part two of Swedish migration policy this weekend!

2 Nov 2012

Posted by Michelle in Expat Life, Identity, Language | 3 comments

I’ve been lucky enough to be able to interview Christof Demont-Heinrich, Associate Professor of Media, Film & Media Studies at the University of Denver about his views on bilingualism, and also his experiences of raising bilingual children.

I first came across Christof on the brilliant sociolinguistics website Language on the Move where I was immediately fascinated by his articles on the costs of raising bilingual children in the United States. What is interesting about Christof is that while his father was German, Christof was raised to speak only English, and learnt German later at university. He now uses the one language one parent approach to teach his two daughters German and English, but as a non-native speaker of German, he has also employed at various times German au pairs, a nanny and then sent his daughters to an international school in the US.

Michelle: Some people from English speaking countries feel that due to English being the (unofficial) lingua franca of the world at present, that being bilingual is unimportant for native English speakers. Why was it important for you to raise your two daughters to be bilingual in the US?

Christof: I believe strongly in the ideal/ethic of meaningful multilingualism for all, including mother tongue speakers of English. I also believe that simply talking about how important multilingualism is — which a lot of well-educated mother tongue speakers of English do — but not actually living that multilingualism in a meaningful way is highly problematic. We need to live that which we preach/believe in, create the social structures and practices we believe in by living them, or they will not come to be. Plain and simple. I recognize this is highly idealistic, of course, and the fact of the matter is that, while a small but also growing percentage of the U.S. population with English as a MT are waking up to the fact that multilingualism has to be lived in order for the ideal to survive, for instance, by building language immersion schools, the vast majority of people for whom English is a MT in the U.S. either have little interest in multilingualism, or, if they do, do not bother to invest themselves significantly in building the social structures and participating actively in the social practices needed to develop multilingualism in a meaningful way.

In short, while I recognize — in a painful way, actually — that instrumental language learning means that very few mother tongue speakers are going to invest in becoming meaningful multilinguals themselves, I want to build a world in which this changes, even if very slowly. I view myself, and the bilingual living and education of my daughters as integral to actively building the multilingual social change I believe in. I’m not so naive as to believe that we, alone, will change much of anything. But if enough people “walk the walk”, then, hopefully, change will happen on an incremental basis. Of course, being somewhat of a natural born pessimist, I often think that what I’m doing is rather hopeless.

Why did you choose the combination English/German?

C: For heritage reasons. My father emigrated to the U.S. from German in the early 1960s. He did not pass his linguistic heritage on to me or my two siblings (my mom is an American who was, when we were kids, an English monolingual). We lived for 8 months in Stuttgart, Germany when I was 7. I went to school then, along with my younger brother, who was 6. I acquired something very close to a native accent as a result of this well-timed experience. However, I never really learned German until college (the late 1980s), when I chose to major in German and I spent a full year studying abroad in Freiburg, Germany.

Why did you choose the one language one parent approach? Would you recommend this approach to other parents who might not be a native speaker of the language?

Everything I have read — and I have read extensively on the topic of raising children bilingual — points toward this being the most effective approach, at least if the goal for the children to use the minority language regularly on an everyday basis and, ideally, acquire high-level spoken fluency in that language (I recognize this is not always the goal for all parents raising their children as multilinguals, that there is a continuum of goals/hopes for the children ranging from a “a few words/sentences” and simply a general appreciation of the minority language to receptive bilingualism only to full-scale, near “equilingualism” for the children. I believe my stubborn and consistent sticking to German — which, as you probably know, is not a first language for me — with my daughters, Alina (7) and Kyra (6) has been absolutely integral to them using German everyday. I’ve seen many situations in which parents, for a variety of understandable reasons, do not stick to one parent one language and, in those case, I see that the children often speak very little German at all. While I think one parent, one language, and sticking to that is absolutely crucial if the goal is high-end spoken fluency and regular use of the minority language and the family situation is one in which only one parent speaks the minority language (that is our situation), I think an even better situation is one in which both parents speak the minority/less powerful language in question, for instance, German in the U.S. In those instances, I would support a two-parent German at home model, frankly.

What have you found most challenging/rewarding?

In terms of challenges, fighting the system, frankly. The entire U.S. public education system is rigged against multilingualism and for monolingualism. Indeed, it’s specifically designed to ensure the erasure of the languages of immigrants who are educated in English only. Because there is only a tiny percentage of public charter schools in the U.S. that offer language immersion program — far less than 1% of schools in the U.S. offer language immersion — and because “our” language, German, is not a powerful language in the U.S. context, we have been forced to send our kids to a private language immersion school. I’ve estimated by the time my daughters are 13, we will have spent $250,000 out of pocket on their bilingual education. This because the American public education system simply does not support bilingualism. Nor does the larger American values system — if we truly valued meaningful, deep multlingualism for all, we would see that reflected in investment in multilingualism in our education system. The monolingual U.S. public education system is nested within a cultural and political environment that is largely indifferent, often very antithetical, to multilingualism, especially actually lived, everyday multilingualism where people actually use multiple languages on an everyday basis in multiple domains outside of the home.

Are there any books or journal articles you would recommend for other parents wanting to raise their children to be bilingual?

I’m going to have to check on this. While I’ve read quite a few, I haven’t kept track of them, for the most part. That’s because my area of research as a professor at the University of Denver focuses primarily on macro-level issues having to do with language, identity, power, culture, globalization, and, especially, the globalization of English as this affects the larger global linguistic configuration of power as well as the question of multilingualism vs. English-centric bilingualism (for those for whom English is a FL) vs. English monolingualism (for those with English as a MT).

Do you want your daughters to spend time living in Germany while they are young? (to become familiar with the German culture as well as the language?)

Yes. In fact, I hope to be spending a sabbatical year at the University of Hamburg with the entire family next year. I hope that everything works out and we are able to do this. Of course, I am aware of the rather large irony that in order to raise my kids as true/meaningful bilinguals I must escape the deep monolingualism of the U.S. education system and place my kids in the largely German monolingual educational environment in German.

Yes, they are clearly learning English in Germany, the students, that is, and they start at a much earlier age than children here do on learning FLs. But in the end, the general environment in Germany, I would say, is still one in which the ideology of monolingualism, in this case monolingualism + English, dominates, e.g. the “modern” nation state model. I ultimately view as the biggest impediment to meaningful and deep multilingualism for large numbers of people around the globe. That is, English isn’t really the problem, it’s the ideology of monolingualism that’s the problem. In global power domains this translates into English only — at academic conferences, etc. However, it could just as easily be another language, had historical circumstances developed differently. And, frankly, I often wish they had (though, clearly, I would not have wanted to see Nazi German triumph — that’s a whole other issue, Germany’s Nazi past, that complicates the whole attempt to raise one’s kids as German-English bilinguals: The vast majority of German educated elites see English as an escape from that past — and I, and my daughters, are literally swimming against all the Germans rushing to English in our attempt to be German-English bilinguals). In any case, if another language had become the global language, then we Americans would be multilingual — because we’d have to be.

Thank you very much Christof!

You can read more about Christof’s views here at Language on the Move.